IN THE GRAINY CELL PHONE VIDEO, Sebastian Woodroffe is struggling to stand. Dressed in jean shorts and a black sweatshirt, he’s lying in a puddle, clearly in pain, moaning and gurgling in the blood and the dirt. If he has not embraced his fate, he has at least acknowledged it. Around him, on a soggy, green clearing in a jungle settlement, a crowd has formed. The villagers, maybe 25 in all, mostly men, scream and shriek. “Why did you kill her, you son of a bitch?!” one bellows in an indigenous tongue. Others stand under the thatched awning of a shack, saying nothing; schoolchildren mill around.

A man in a baseball hat then tries to loop a seat belt around Woodroffe’s neck. He throws it off. The man tries again and gets the noose tight around Woodroffe’s throat. Someone shouts, “Pull, pull!” and the man does. He and a partner drag Woodroffe into the grass. Woodroffe is lying facedown now, arms at his side, no longer struggling. The man holding the end of the noose drops it. Then Woodroffe lifts his head, and the man snatches the noose and pulls it tight again and again. Then the video cuts off.

ON APRIL 21, 2018, THE FOOTAGE WAS posted to the Facebook page of a Peruvian news outlet. When local authorities saw it, they knew immediately who the white man was. For the past 48 hours, they’d been searching for Woodroffe—ever since an 81-year-old shaman named Olivia Arévalo Lomas had been shot and killed in Victoria Gracia, a village of indigenous Shipibo-Conibo people, in the remote Ucayali region of northeastern Peru. Police had found her lifeless body beneath a coconut tree, with two bullet holes in her chest and three spent .380 ACP cartridges a few yards away. The villagers had been emphatic that the killer was the “gringo.” But Woodroffe was nowhere to be found.

After viewing the clip, officers returned to Victoria Gracia, where they discovered Woodroffe’s body about 700 yards from the village. Wrapped in a blue sheet, he had been buried hastily in a two-foot grave. His face was swollen. His body was purple with bruises. His clothes were coated in dirt and dried blood.

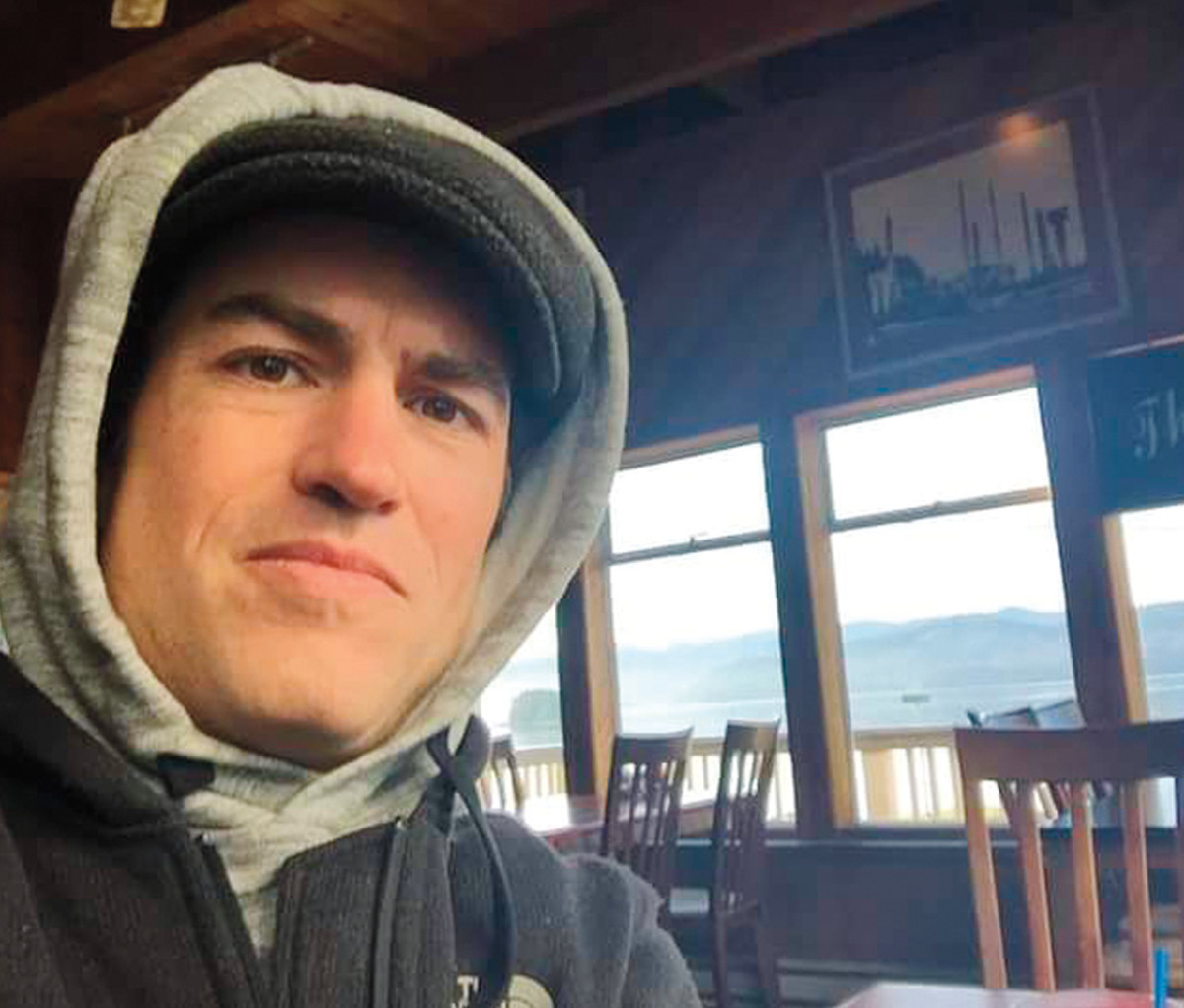

Woodroffe, 41, was a handsome, free-spirited father of a 9-year-old son who had, a few years before, developed an affinity for the drug ayahuasca—a sludgy, hallucinogenic brew made from Banisteriopsis caapi vines and chacruna leaves. The concoction has been consumed in the Amazon basin for centuries, and now each year, thousands of foreigners—mostly from North America and Europe—travel to the region to indulge in its psychedelic properties. In trekking to Peru, Woodroffe had intended, ostensibly, to study under local shamans, to “fix [his] mind,” as he wrote on Facebook.

Olivia Arévalo, meanwhile, was not only a grandmother figure to the villagers of Victoria Gracia but also a spiritual matriarch to the Shipibo-Conibo people—one of the largest tribes in the Peruvian Amazon, with 20,000 members, concentrated around the Ucayali River. The descendant of a long line of healers, she knew some 500 herbal remedies and was, to the younger villagers, one of the last links to their dying tribal culture. “She had the power to calm storms and strong winds,” villager Nestor Castro later told me.

In the following days, the seemingly senseless murder of Olivia Arévalo and Woodroffe’s brutal execution became international news. CNN, The Guardian, The Washington Post, and Vice all picked up the story. The Peruvian newspaper La República wrote that Arévalo’s murder was the death of Shipibo culture incarnate. And in Woodroffe’s native Canada, the papers focused on his friends’ and family’s disbelief. “It is absolutely not something he is capable of in any way,” a friend named Alison Jones told Global News.

The murders also sparked intense debate among a burgeoning community of ayahuasca users. On Web forums, like DMT Nexus, commenters seemed split. Many condemned the tribe for taking justice into its own hands. But others laid the blame squarely on Woodroffe. “There is rampant racism, xenophobia, and misogyny in the community (which is overwhelmingly made up of young, white Euromerican men and boys),” one user wrote. These men, the commenter continued, “appropriate things they have no honest knowledge or understanding of.” An expat blogger responded similarly, accusing Woodroffe of being woefully naive about the realities of tribal life in Latin America.

Ricardo Jimenez, the lead prosecutor in the Ucayali region, told me that once Woodroffe’s body was found, forensic experts quickly pieced together that he had indeed killed Olivia Arévalo, as the villagers alleged. Officers discovered his silver Taurus handgun buried in a nearby cemetery, and forensic experts matched empty cartridges found near Olivia Arévalo’s body with the gun. Gunshot residue was also discovered on the sleeves of Woodroffe’s sweatshirt. But what remained uncertain was how Woodroffe had become so lost and descended into such darkness, and whether ayahuasca had played a part.

SEBASTIAN WOODROFFE WAS BORN IN Barrie, Ontario, in 1976. From a young age, he was a prankster who took pleasure in getting friends out of their comfort zones, whether by climbing mountains barefoot or getting lost in the woods. He wanted people around him to experience “amazing things,” his sister, Jaime Woodroffe, told me recently. He was affable and popular, the kind of guy, she said, who on short walks to the store would repeatedly get stopped by friends.

As an adult, Woodroffe never had much direction in terms of career. He drifted between jobs in construction, tree planting, and sea-urchin diving. In his early 30s, he had a son, but his relationship with the child’s mother didn’t last. “He thought he lost the one,” Jaime said. According to several of his friends, Woodroffe remained a committed father—although he never embraced traditional family structures and was never entirely comfortable with the typical expectations of how a man should act or behave, a neighbor later told a Canadian paper. But Andy Woodsmith, one of Woodroffe’s longtime friends, told me that this was what he admired most about Woodroffe. He was a dreamer and had always been a bit different, but “he was never afraid to be exactly who he was,” Woodsmith said.

According to friends and family, Woodroffe cared little about material things. For him, having oneness with nature, not money or social acclaim, was the key to happiness and well-being. Since his early teens, he had “scrambled about the rainforests of [his] home [on Vancouver Island], identifying and consuming the plants,” he once wrote. He later told followers of his video blog, The Sacred Circle, “Get your shoes on, go out into the woods, and talk to the plants, talk to birds.”

His love for the outdoors complemented his strong spiritual side. In time, Woodroffe became interested in indigenous North American cultures; he even participated in an annual sun-dance ceremony, a brutal ritual of physical punishment and fasting. In one part of the dance, participants tether themselves to a pole by piercing a hook through their chest; Woodroffe liked to show friends his scars. Rituals like this, along with teaching his young son about nature, gave Woodroffe purpose. But his sister told me that, above all, he cared about improving the lives of people close to him; friends agreed.

Everything changed for Woodroffe in 2013. That year, his family staged an intervention for one of his relatives who had been struggling with alcoholism. For Woodroffe, the experience was revelatory. He began to think deeply about addiction and suffering. “The drink problem comes not from the drink itself but the family,” he said on his video blog. “There are so many unresolved issues, so much trauma; it’s as if the spirit of [our] family has been hurt.” And Woodroffe wanted to heal the wound.

He decided to become an addiction counselor. “Never before has a path been so clearly laid out for me,” he wrote online. As he pursued his new vocation, he remained committed to his free-spirited nature, showing little interest in Western medicine. He alleged that modern treatments worked for only 5 to 8 percent of people, “a rather dismal outlook for those working in, and hoping to receive help from, these programs.” Old ways of thinking, he believed, were preventing alternative methods, like plant-based medicines, from playing a larger role in treatment. “I want to integrate knowledge and healing from other parts of the world to help bring these numbers up,” he wrote.

One of the remedies he had in mind was ayahuasca. According to the CBC, he discovered the drug through his brother-in-law, who had tried it at a ceremony in Whistler, British Columbia. People who take ayahuasca tend to have surreal visions and vomit violently. But the effect, Woodroffe learned, can be therapeutic and help to treat severe depression, along with other mental-health issues.

In late 2013, he launched a crowdfunding campaign to help bankroll his career change as an addiction counselor focused on plant-based medicine. He raised just over $2,000 Canadian, then, in September 2014, traveled to the Peruvian jungle city of Iquitos, to study under ayahuasca shaman Guillermo Arévalo (one of Olivia Arévalo’s cousins). Woodroffe was “a good person,” Guillermo Arévalo told me, “although one struggling with trauma.” He didn’t care to elaborate, but the trip no doubt fueled Woodroffe’s desire to learn more about ayahuasca.

Over the next three years, Woodroffe made several more trips to Peru and continued to take ayahuasca in ceremonies near his hometown. But he soon seemed disillusioned with life. Friends said that he could be distant and erratic. In Facebook posts in 2016 and 2017, he professed to feeling “lonely” and “low,” and wanting “to be with friends.” Some people I spoke with figured that Woodroffe was struggling with a breakup from a recent girlfriend. But others thought that his quest to become a healer, and his trips to Peru, were causing him problems, and perhaps creating a disconnect between his fantasies of becoming a spiritual healer and the everyday grind of life.

A friend, who spoke to me on the condition of anonymity, said that Woodroffe was indeed charming and essentially a good person. “He looked after me on many occasions,” the person said. But, beneath the surface, he also had a temper and could be volatile and obsessive. Ayahuasca changed him, the person seemed sure. He started dieting constantly—not consuming salts or sugars—and lost a lot of weight. “I could see how he could get himself into a lot of trouble in Peru and not back down if he felt he was right,” the person added. Andy Woodsmith, another friend, wasn’t sure whether ayahuasca was to blame for Woodroffe’s turn, but told me, “[Sebastian] was committed—sometimes to a fault—to sticking to his heart path.” When his father, Gary, advised his son to seek professional help, Woodroffe only withdrew further.

SEVERAL MONTHS AFTER THE MURDERS of Woodroffe and Olivia Arévalo, I stood in the center of Victoria Gracia. The village, sprawled across a dusty flatland, comprises a hundred or so wooden houses, hemmed in on all sides by monkey brush and coconut and palm trees. The residents are poor. They have no running water or electricity mains, and the women make and decorate clay pots. But the community isn’t free of modern influence. Most of the villagers dress in Western clothes, own generators and cell phones, and follow European soccer clubs.

Becky Linares, the community leader, told me that if I wanted access to the settlement, I first had to present myself at the village’s weekly assembly. So, standing under a hulking tree, I found myself surrounded by a hundred dead-eyed stares, belonging to the same people who had witnessed Woodroffe’s lynching, and had perhaps participated. They were not shy to tell me that neither outsiders, like me, nor the Peruvian government actually cared about their poverty; or their children’s poor education; or that gangs, logging companies, and oil speculators had forced them to leave their homes deeper in the rain forest; or that their culture was being debased by “ignorant gringos.” “Journalists never come here—never!” one man shouted. “But after the Canadian died, this place was full of them.” It wasn’t Olivia Arévalo’s death that people cared about, he said.

I wasn’t surprised by these accusations. Ayahuasca tourists, who have been arriving from North America and Europe since at least the 1960s, have long been accused of appropriating and dishonoring indigenous tribal culture, by using the brew, an important part of local religious ceremonies, for recreation. The recent boom in ayahuasca-seeking outsiders owes, in large part, to scientists’ speculations that DMT, the drug’s primary psychoactive substance (which is illegal in the U.S. and Canada), may help treat addiction, depression, post-traumatic stress, and other disorders. A 2015 study, involving advanced MRI scans of 10 experienced users, showed, for one, that ayahuasca can decrease activity in the brain’s so-called default mode network, alleviating apprehension and anxiety, and inspiring introspection. Yet other studies, including one published in 2017 in The Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, have indicated that DMT can also exacerbate preexisting mental illnesses, such as bipolar disorder.

More research is needed to fully understand ayahuasca’s effect on the brain. But, over the past decade or so, as a result of the drug’s widely touted benefits, hundreds of shamanic schools and ayahuasca retreats, many run by North American and European expats, have popped up that promise to cure all manner of ailments, while providing a mind-expanding experience. The most profitable retreats in Iquitos, Peru’s largest jungle city, bring in nearly $6 million annually and charge guests as much as $2,700 for a week’s stay, according to Carlos Suárez Álvarez, the author of Ayahuasca, Iquitos, and Monster Vorax. Proponents of the drug claim that the ayahuasca boom has helped to revive tribal culture and injected much-needed revenue into indigenous communities. But locals I spoke with disagreed. Ronald Suárez, a Shipibo-Conibo leader, told me that ayahuasca tourism has become an industry churning out a product for wealthy foreigners, “turning our medicine into a recreational party drug.” Native communities view the rain forest as a living thing, many locals told me, whereas outsiders have historically regarded it as a warehouse of gold, lumber, and oil worth exploiting—and that ayahuasca is no different. “This harms our culture very badly,” Suárez said. Now, in many of these communities, there is only suspicion and fear of the foreigner, he said.

Nowadays, ayahuasca can be found around the world—Brooklyn, Silicon Valley, Madrid. But the Amazon remains the epicenter. Although the ayahuasca ritual was declared part of Peru’s national heritage in 2008, the country has no formal guidelines for how a ceremony should be conducted, nor any governmental body regulating who can conduct one. In Pucallpa, the nearest city to Victoria Gracia, I saw ayahuasca sold in Coke bottles at markets, advertised on posters, and peddled by rickshaw drivers. According to author Carlos Suárez Álvarez, over the past decade, as demand has increased, the cost of ayahuasca has as well, going from about $10 a session to 10 times that, and often much more. And as the price of ayahuasca has risen, so has the number of pseudo-shamans. “It takes years to become a shaman,” Pedro Tangoa, a renowned Shipibo shaman, told me. “It requires patience and deep knowledge of plants and herbal remedies. These fake shamans have no idea what they are doing.” They see ayahuasca as a business opportunity, he said, and, as such, “often mix the ayahuasca with other, more volatile plants, such as toé and floripondio, to create a more explosive trip” for tourists.

Top ayahuasca retreats focus on healing their guests, offering experienced, trusted shamans, comfortable rooms, and assistants on hand to help guests, should their trip take a bad turn. But, with shady pseudo-shamans, “when something goes wrong, they don’t know how to help the patient,” Tangoa said. “A good shaman is capable of snapping a patient out of a dangerous trance in an instant.” Participants in shady ceremonies have been robbed and molested, and become violent or sick. According to Peruvian news outlets, over the past decade, at least 11 tourists have been killed in incidents linked to traditional medicine—including Kyle Nolan, an 18-year-old American, who, in 2012, was secretly buried by a shaman after he died in an ayahuasca ceremony. In December 2015, during a ceremony at a retreat in Iquitos, a British man started waving around a kitchen knife and screaming; a Canadian man, also on ayahuasca, managed to grab the blade—then stabbed the man to death.

In September, I visited Douglas Tangoa, an apprentice shaman and son of shaman Pedro Tangoa, in a tarantula-infested log cabin deep in the rain forest, next to a lagoon crowded with caimans. Tangoa and his friend César Coquinche Hoyos, each dressed in a traditional tunic, were preparing an ayahuasca ceremony. They puffed on wooden pipes and muttered incantations into a thick, brownish brew. “By itself, ayahuasca can do you no harm,” Tangoa told me. “It is like a scanner that allows the shaman to find out exactly what is wrong with his patient.” But neither man would allow me to take ayahuasca; I hadn’t done the proper dieting in preparation, they said. Many shamans recommend that, before consuming ayahuasca, users avoid a somewhat odd mix of vices—caffeine, carbonated drinks, red meat, salt, sex, sugar—for a week beforehand. If the ayahuasca process is tampered with or rushed, “that’s when the patient can have adverse reactions,” Tangoa said.

Mixing the brew with alcohol, recreational drugs, or certain medicines, as some ill-informed users have done, is another way to invite problems. Charles Grob, a professor of psychiatry at Harbor-U.C.L.A. Medical Center, has linked the combination of serotonin-based antidepressants and ayahuasca to an illness called serotonin syndrome, which begins with shivering and palpitations and can lead to seizures and even death. Moreover, according to Dennis McKenna, an ethnopharmacologist and research pharmacognosist, the stress of traveling, especially in a foreign country such as Peru, can result in a negative experience and even trigger violent reactions. McKenna stresses the importance of using ayahuasca in a safe, familiar place, in the company of a trusted shaman who can help contextualize the experience afterward. “I think that’s probably what happened to [Woodroffe], and it’s tragic,” McKenna said. “He did not receive the right support, preparation, or integration, which could have mitigated this.”

IN LATE 2017, WOODROFFE SET OFF FOR Peru again, still determined to become a healer. But whether he was trying to cure himself or other people is difficult to know. Instead of returning to Iquitos, as he had on past trips, he traveled to Pucallpa, a smaller city, where he rented a room. Nelly Vázquez, one of Olivia Arévalo’s granddaughters, remembers the day that he arrived in Victoria Gracia. “He wanted to do ayahuasca with my grandmother,” she recalled. “He told me he was sick, that he was crazy.” She was hesitant to help Woodroffe; he seemed strange and frantic. But when he said that one of her relatives, shaman Guillermo Arévalo, had sent him, she agreed to introduce Woodroffe to her grandmother. Woodroffe, who didn’t speak Spanish, had come with a local taxi driver named Herbert, who translated. He asked whether Olivia Arévalo’s powers could reach as far as Vancouver and cure his whole family. Olivia Arévalo assured him that they could.

Over the next month, Woodroffe returned to Victoria Gracia numerous times. “He was always coming around—sometimes during the day, sometimes during the night,” Nelly said. Another villager remembered him turning up in the village at midnight intoxicated, brandishing a club that he used to threaten her friends. Miluska González, another villager, claims that Woodroffe was always in the village drinking beer. Locals began to call Woodroffe pela cara (face peeler) and pishtaco (bogeyman). They allege that, as his behavior became increasingly troubling, they told him to not return, but he did anyway. They also claim that they reported him to the police on at least two occasions, and even detained him, but that the authorities did nothing. (Police told me that they have no record of complaints from the village.)

It’s hard to know how much ayahuasca Woodroffe was taking during this period; several villagers allege that he stopped taking it when he visited, and autopsy reports were inconclusive about whether the drug was in his system at the time of his death. And it’s impossible to know whether Woodroffe’s alleged erratic behavior was directly linked to the drug. But almost everyone I spoke with agreed that his frequent visits were connected to one man: Julian Arévalo—Olivia Arévalo’s son. Investigators now believe that the men had some sort of business relationship, perhaps involving their starting an ayahuasca retreat together. But things had soured. In January 2018, Woodroffe returned to Canada, but by March, he was already headed back to Peru, writing on Facebook beforehand that he was off to the jungle to do some soul-searching—“see you when I am healed.”

Simon Donald, an English expat who lives and works at an ayahuasca center near Pucallpa, remembers the day, in late March 2018, when Woodroffe turned up looking for Julian. Shamans asked him to leave the center, but Donald agreed to meet Woodroffe at a coffee shop the next day to talk things out. When they did, Woodroffe didn’t offer much. “He seemed like a nice enough guy,” Donald said. “He just thanked me for trying to help and left.”

Then, a few days later, Woodroffe wandered into a police station near the center of Pucallpa, asking to buy a gun. The decision was strange; this was by no means the normal way of buying a firearm in Peru. But, according to local newspapers, Woodroffe had been trying for months to get hold of a gun. The police, it seemed, were a last resort. Communicating via Google Translate, Woodroffe told an officer that he was going into the jungle and needed protection from animals. Curiously, the officer agreed to the sale, mainly because “the gringo was offering such a high price,” the man later said in a statement. On April 3, Woodroffe returned to the police station and paid 3,000 soles, or about $900, for a silver, Brazilian-made Taurus handgun. Carlos Vilcahuamán, the acting magistrate in charge of the investigation, described the purchase as abnormal but not illegal.

Woodroffe’s intention for buying the gun remains unclear. He didn’t use it when he turned up in Victoria Gracia on April 10, looking for Olivia Arévalo Lomas. And there’s no indication that Woodroffe had it when he was accosted four days later while out drinking beers. (According to police reports, he claimed that two men dressed as police officers stole his backpack.) Nor did the gun appear the day before the murder, when, according to Olivia Arévalo’s daughter Virginia Vásquez, Woodroffe turned up in Victoria Gracia, holding a sign, written in Spanish, that said Julian owed him 14,000 soles, or about $4,000. Vázquez told the local press, “My brother would have never borrowed money like that.”

On April 19, 2018, Woodroffe spent the morning alone in his rented room, with its whitewashed walls and cold tile floor. On his desk was the book The Happiness Equation and three orange prescription bottles: sleeping pills; Klonopin, for panic and anxiety; and Olanzapine, an antipsychotic. Somewhere nearby was the Taurus handgun.

By 10:30, he was speeding through the rain forest on a borrowed red motorbike, following a rutted road that cut through the forest. His neighbor, Guillermo Sanchez, hadn’t thought it odd when Woodroffe borrowed his Zongshen motorcycle that morning. He’d always found Woodroffe to be friendly and respectful, and had no reason to think that he was up to anything peculiar.

Woodroffe arrived in Victoria Gracia at noon. Once at the center of the settlement, he stopped at a gray wooden house, then took off his helmet and climbed off the bike. “Julian,” he yelled over and over, according to authorities. When Julian Arévalo appeared at the window, Woodroffe fired. The shot echoed through the village. As Julian ran, inside an adjacent dwelling, 81-year-old Olivia Arévalo went out her back door to investigate the commotion.

The other villagers quickly spotted Woodroffe and dashed toward him, shouting. He turned to escape—but found Olivia Arévalo, confused by the unfolding scene, blocking his way. Panicked, he fired once. Then again. The old woman fell to the ground. Woodroffe scrambled back to his bike and tried to start the engine. But the switch was tricky; he always had trouble starting it, his neighbor told me. As the villagers closed in, Woodroffe forced the engine to life and sped off along the rutted dirt road. But he hit a dip and lost control. Then he was surrounded. Some villagers wanted to take him to the police. But their petitions were ignored. According to police reports, as Olivia Arévalo lay dying beneath a coconut tree, embraced by a daughter, she said, “They’re killing me. They’re killing me.”

SIX MONTHS AFTER THE DOUBLE MURDER, Carlos Vilcahuamán, the district prosecutor in Pucallpa charged with overseeing the investigation, told me that he was frustrated that the four suspects in Woodroffe’s lynching, as identified in the grainy Facebook video, hadn’t been apprehended. “They’re still hiding in the jungle,” he said. His consolation was that he was sure of who’d killed Olivia Arévalo. “All the evidence points to Woodroffe firing those shots that day.”

Despite the media attention the killings received, interest in ayahuasca, and venturing into the Amazon to use it, shows no sign of waning. Ayahuasca’s promise of inner peace and self-awakening outweighs whatever negative side effects or risks it may carry, Guy Crittenden, author of The Year of Drinking Magic, told me. The thousands of people who flock to the Amazon to use the drug do so with good intentions, he said, and most come to respect the indigenous practices. But these people arrive in a culture that they do not know and that does not know them.

Nelly Vázquez, for her part, said that her grandmother’s death has made her more suspicious of outsiders—even if Woodroffe was an anomaly. Before he came, “we lived a peaceful life,” she said. “We didn’t bother anyone.” Now she feels haunted by “the gringo.”

The ayahuasca community, meanwhile, has made efforts to acknowledge the murder of Olivia Arévalo. Alan Shoemaker is a senior figure in the community, based in Iquitos. He said that he moved his annual shamanism conference to Pucallpa in honor of the dead shaman; he wanted to show the Shipibos “that gringos are not insane,” he said, and told me that people are forgetting about what happened. Cielo Tierra, an Australian expat and the owner of the retreat Casa de la Madre near Pucallpa, echoed the sentiment. “No one is talking about it anymore,” she said. And perhaps more important, she added, she hasn’t noticed a drop-off in ayahuasca visitors. “No, it hasn’t affected my numbers here,” she said.

Read the ORIGINAL article at : https://www.mensjournal.com/features/blurred-vision-a-shamans-murder-uncovers-the-dark-side-of-ayahuasca/